In late 2020, online spices retailer Spiceology.com was changing ecommerce platforms but ran out of time before the holiday season to complete the process.

The retailer’s contract with its new vendor, BigCommerce, included making sure the ecommerce website was fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Spiceology got about 70% there before it had to lock down the website changes and go live in preparation for Black Friday.

“We had to make a business decision,” says Chip Overstreet, Spiceology’s CEO. That decision, he says, was to finish the ADA compliance work in early 2021, after the holiday rush concluded. But 70% wasn’t good enough. The retailer quickly faced a lawsuit.

Spiceology isn’t alone. The number of website accessibility lawsuits in the United States is rising, and retailers face such suits far more than other kinds of organizations, an analysis of cases filed in 2020 finds. The study from UsableNet Inc. found the number of digital accessibility cases grew to 3,503 in 2020, up 21.2% from 2,890 in 2019. According to the report, 77.6% of digital accessibility lawsuits last year cited retailers. UsableNet creates web accessibility tools and platforms. On its website, UsableNet lists retailer clients, including J.C. Penney Co. Inc. (No. 31 in the 2020 Digital Commerce 360 Top 1000).

The UsableNet study analyzed digital accessibility-related lawsuits involving websites, mobile apps, or video content subject to a claim in federal courts under the ADA or California state courts under the state’s Unruh Civil Rights Act.

The ADA, signed into law in July 1990, is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on physical or mental disabilities. The Unruh Civil Rights Act, enacted in 1959, bans discrimination based on sex, race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, age, disability, medical condition, genetic information, marital status, sexual orientation, citizenship, primary language, or immigration status in California.

For online retailers, this means that their websites must be “meaningfully accessible” to all shoppers, such as those who are blind or visually impaired, have seizure disorders or cope with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). For blind or visually impaired shoppers, retailers might offer a version of their site with enhanced visuals and make the site compatible with screen-reading technology. For those with seizure disorders, merchants could offer a website version that eliminates flashes and reduces color. Users with ADHD could get the option to see focused content with fewer distractions than the site otherwise would have.

UsableNet researchers found plaintiffs filed almost 93% of the lawsuits in three states: New York (49.5% of the total), California (27.9%) and Florida (15.3%). That doesn’t mean the companies sued had their headquarters in those states, only that they do business in them. Also, just 10 law firms brought about 70% of all digital ADA cases last year.

Jason Taylor, chief innovation officer at UsableNet, says more than 66% of the retailers listed in the 2019 version of the Digital Commerce 360 Top 500 were named in an ADA web or app-accessibility cases from 2017 through 2019. Of those sued, more than 40% faced more than one lawsuit, he says.

Why retailers are vulnerable

Taylor at UsableNet says plaintiff law firms target retailers more often than other website operators for several reasons, he says. “To set some context, most lawsuits are brought by the 12 most active plaintiff lawyers and their clients, so this is a volume activity. They look to target similar sites that generate similar claims,” he says. Retailers became the top target for ADA-related suits for three key reasons, he says:

- Retail websites are popular web destinations and easy to visit. Because of that, “it’s very easy to visit retail stores online, download apps, and experience whether a company has done a good job of making the digital property accessible,” Taylor says.

- Existing United States Department of Justice (DOJ) settlements have set precedents that say retailers must provide accessibility. So, plaintiffs can cite past DOJ actions in which retailers agreed to update their websites to match ADA requirements.

- It can be challenging for retail sites to reach and maintain the World Wide Web Consortium’s widely used Web Content Accessibility Guidelines standards. Because retail websites and mobile apps are notoriously complex, accessibility fixes can present financial and logistical challenges. Likewise, the requirements of the WCAG can be detailed and lengthy, making it easy for retailers to make mistakes.

Watch out for the ‘vermin’

“I don’t want to in any way diminish the value of ADA compliance. I think it makes a lot of sense,” Overstreet says. But he adds that the plaintiffs’ law firms in digital accessibility cases are “vermin” that actively seek out companies to sue and file numerous lawsuits at once. And while the law firms know what they are doing, many retailers hit with such litigation don’t know how to react. For that reason, Overstreet says, retailers facing digital accessibility litigation should be careful to avoid possible scams.

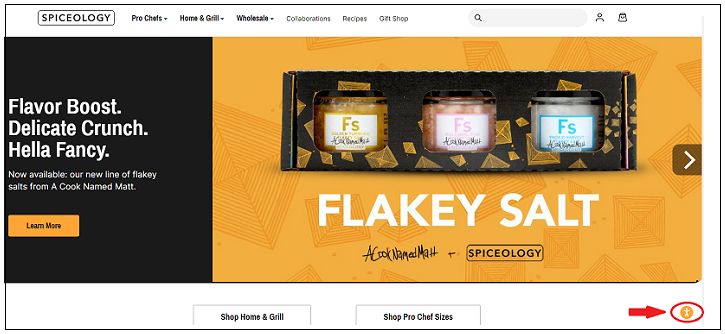

Visitors to Spiceology’s website can bring up a menu of options for adjusting the site’s content to make it meaningfully accessible to people with various disabilities.

“As soon as that lawsuit gets filed, there’s a second set of vermin that are out there waiting to pounce. And those come in many categories,” Overstreet says.

That second wave, he says, includes lawyers who specialize in defending retailers in such cases, consultants and compliance vendors—some of which might not be legitimate. “The bids that you get from these various organizations are far and wide and it’s nearly impossible to sort through who’s credible and who is just trying to profiteer,” Overstreet says. “So, it really comes down to knowing where to go.”

In Spiceology’s case, the retailer decided to use an Israel-based vendor called accessiBe LTD, which offers technology intended to address accessibility issues. AccessiBe has “been phenomenal,” Overstreet says.

Thanks to the vendor’s technology, visitors to Spiceology’s website can click on an icon to bring up a menu of options for adjusting the site’s content to meet their individual needs. The cost, Overstreet says, is “a couple of hundred bucks a month.”

Important court decisions

Federal courts have, in recent years, upheld the right of disabled people to sue over website and mobile app accessibility. For example, in January 2019, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Robles v. Domino’s Pizza that a visually impaired consumer could sue the pizza chain, claiming the Domino’s website and mobile app failed to comply with the ADA’s standard. The three-judge panel held that “the ADA mandates that places of public accommodation, like Domino’s, provide auxiliary aids and services to make visual materials available to individuals who are blind.”

In October 2019, the United States Supreme Court declined to review the Domino’s Pizza case, thus allowing the Ninth Circuit decision to stand. After that, Taylor says, digital accessibility lawsuits spiked.

“Leading up to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision not to hear the case, the number of lawsuits filed decreased to 30 per week. However, once the Supreme Court decided that the decision would stand, the rate of lawsuits increased exponentially again,” Taylor says. “Interestingly, after Robles, we are seeing more lawsuits for apps and mobile app websites,” he added.

William Goren, an attorney, consultant and blogger who specializes in ADA-related issues, says the South Dakota v. Wayfair case—in which the Supreme Court ruled states have a right to charge tax on web purchases from out-of-state sellers—has important implications for web accessibility.

To understand how the Wayfair case affects accessibility, Goren says, it’s important to know “being compliant” with the ADA is a misnomer. The true legal standard is whether a website or other place of business is “meaningfully accessible” to users with disabilities; no detailed regulations exist that specifically define what that means, he says. However, courts and the DOJ increasingly view websites as places of business, equivalent to stores, he says.

In the Wayfair case, the court found Wayfair’s ecommerce site is “every bit a place as a physical store,” Goren says. Stores—as places of public accommodation—must be able to be meaningfully accessible to people with disabilities. If websites also are public accommodations, they have the same obligation, he says.

“The trend is that if you are doing one of the things that makes something a place of public accommodation—under the definition of what is a public accommodation under the ADA—then your internet site has to be meaningfully accessible to people with disabilities,” Goren says.

However, while the law isn’t specific, web designers have a commonly accepted set of best practices or website accessibility. The WCAG guidelines are the “gold standard,” Goren says. But those guidelines don’t have the force of law. Thus, following WCAG standards does not guarantee that all users will have meaningful access in all cases, he says.

According to legal information website FindLaw, the ADA “defines public accommodations as private entities that own, operate or lease places of public accommodation. Examples of public accommodations include stores and shops, restaurants and bars, service establishments, theaters, hotels, recreation facilities, private museums and schools.”

What retailers should do

UsableNet’s Taylor says it’s essential for retailers to do some research accessibility vendors rather than just sort through unsolicited sales pitches.

When selecting an accessibility vendor to help, we would suggest you ask your ADA lawyer for a list of vendors they have worked with and like the services,” Taylor says. “You should look for vendors that have worked in our industry with similar size companies and are familiar with similar systems you use such, as your commerce platform and general IT platforms.”

He warns retailers from going after what might seem to be easy, quick answers.

“If you’re researching how to make your site more accessible right now, you’ll likely see plenty of services online promoting accessibility widgets or overlays,” Taylor says.

Cookie-cutter widgets and plugins don’t consistently deliver an equivalent experience for everyone. Also, issues like navigation and delivery selection are complex and not easily addressed using artificial intelligence. That means it’s best to use human testers to examine the website to ensure a good experience for disabled shoppers.

In addition, each retailer must consider the accessibility of its entire online presence, Taylor says. That includes mobile websites, native apps and videos—and not just the desktop site. Another consideration, he says, is the need to stay up to date as accessibility standards evolve.

“Accessibility is not a one and done. You want to remediate your websites and apps… even through code changes, new releases, and other business shifts, plan to maintain accessibility on all your digital assets,” he says.

Taylor says the real goal isn’t just to avoid lawsuits but to provide an excellent customer experience.

“In the end, it shouldn’t just be about conformance with WCAG and ADA guidelines. You want a vendor that will ensure your website is usable for people with disabilities,” he says.

Favorite